Moore’s Notes on Wittgenstein’s Lectures, Cambridge 1930-1933:

Text, Context, and Content

David Stern, Gabriel Citron and Brian Rogers

Abstract

Wittgenstein’s writings and lectures during the first half of the 1930s play a crucial role in any interpretation of the relationship between the Tractatus and the Philosophical Investigations. G. E. Moore’s notes of Wittgenstein’s Cambridge lectures, 1930-1933, offer us a remarkably careful and conscientious record of what Wittgenstein said at the time, and are much more detailed and reliable than previously published notes from those lectures. The co-authors are currently editing these notes of Wittgenstein’s lectures for a book to be published by Cambridge University Press. We describe the materials that make up Moore’s notes, explain their unique value, review the principal editorial challenges that these materials present, and provide a brief outline of our editorial project.

Table of contents

1. Context: The middle Wittgenstein

The co-authors of this paper are currently editing G. E. Moore’s notes of Wittgenstein’s Cambridge lectures, 1930-1933, for a book to be published by Cambridge University Press. In this paper we examine the importance of Wittgenstein’s 1930-33 lectures in the context of the development of his philosophy more generally, and in the context of contemporary scholarly debates about how best to understand Wittgenstein’s later thought; we describe the text of Moore’s notes, explaining their unique value as records of Wittgenstein’s 1930-33 lectures; we briefly review the varied and wide-ranging content of the lectures; we discuss Moore’s role in the lectures themselves and in responding to their content; and finally, we outline the principal editorial challenges that these materials present, and provide a brief outline of our editorial project.

In 1929, Wittgenstein returned to Cambridge and philosophical writing, criticising his own earlier work and turning his focus to how language is used in ordinary life. These years were a time of transition between his early and his later work, and are of great interest for anyone who wants to understand the development of his thought.

Wittgenstein’s writings and lectures during the first half of the 1930s play a crucial role in any interpretation of the relationship between the Tractatus and the Philosophical Investigations. The manuscripts from 1929 record his first steps away from the Tractatus; by the end of 1936, he had written an early version of the Philosophical Investigations.

In recent years, the development of Wittgenstein’s philosophy during the first half of the 1930s has attracted increasing attention. One group of Wittgenstein interpreters, including Gordon Baker, Peter Hacker (Baker and Hacker, 1980, 1980a, 1985; Hacker 1990, 1996, 2012) and Hanjo Glock (1996), maintain that Wittgenstein’s later philosophy emerged in the early 1930s, and that it is already clearly stated in works by Wittgenstein and Waismann from 1932-34 (see Baker’s preface to VW 2003). According to this reading, we can already find clear formulations of many central commitments of the later Wittgenstein in his “middle period” writings. Others have argued that Wittgenstein’s thought was rapidly changing during 1930-34, and should not be taken as a blueprint for his later work. According to this alternative reading, Wittgenstein was drawn, during this transitional period in the early 1930s, toward a conception of philosophy on which its aim is to clarify, in a systematic way, the rules of our language in a philosophical grammar. However, by the time he composed the first draft of the Philosophical Investigations in 1936-37 he had given up this conception of philosophical grammar in favor of piecemeal criticism of specific philosophical problems. Versions of this reading can be found in work by David Stern (1991, 2004, ch. 5.2, 2005), Joachim Schulte (2002, 2011), Alois Pichler (2004), and Mauro Engelmann (2011, 2013). Cora Diamond (1991) and James Conant’s ‘resolute’ reading, with its insistence on the unitary nature of Wittgenstein’s thought, initially seemed to be incompatible with the view that there were such major changes in his philosophical outlook during the 1930s (see Hacker 2000). However, in recent years both Diamond (2004) and Conant (2007) have written at some length on the significance of the continuities and discontinuities in Wittgenstein’s work during these years. (For further discussion of Wittgenstein in the 1930s, see Stern forthcoming.)

Despite these far-reaching disagreements about how to understand Wittgenstein’s work during the first half of the 1930s, there is widespread agreement about the importance of Wittgenstein’s work during these years for an understanding of his work as a whole. However, with the notable exception of the Blue and Brown Books – a pair of texts dictated during the 1933-34 and 1934-35 academic years – most of the material that has been published to date is too dense and intricate to be easily accessible. While the Philosophical Remarks, Big Typescript, and Philosophical Grammar are carefully composed, they never reached a polished and final form. Bertrand Russell read about a third of the Philosophical Remarks just after spending five days in discussion with Wittgenstein in the spring of 1930, and he reported that it “would have been very difficult to understand without the help of the conversations” (WC 2008: 183). In fact, all three of these books are best understood as works in progress that were never completed, or as selections and rearrangements from the source manuscripts.

Unlike his personal philosophical notebooks, Wittgenstein’s lectures were explicitly intended to introduce his new thought to people who were unfamiliar with it, many of whom were philosophical novices. We might expect, therefore, that an accurate record of Wittgenstein’s lectures from the early 1930s would be extremely valuable in gaining a good grasp of his developing thought.

2. Text: The particular value of Moore’s notes of Wittgen-stein’s Cambridge lectures, 1930-331

From January 1930 onward, Wittgenstein gave regular lectures and discussion classes during the Cambridge term. G. E. Moore, who became a Professor at Cambridge in 1925, regularly attended most of Wittgenstein’s lectures during the 1930-33 period, and took “very full notes” (MWL 1993: 49), filling six manuscript volumes, which currently reside in Cambridge University Library. These notebooks provide us with both the most comprehensive and the most accurate record that we have of those first three crucial years of Wittgenstein’s teaching in Cambridge. In Moore’s six manuscript notebooks, we have a remarkably careful and conscientious record of what Wittgenstein said at the time. As Moore himself put it in the introduction to his articles on the lectures, written twenty years later, he had “tried to get down in my notes the actual words he used” (MWL 1993: 50).

While Wittgenstein spent a great deal of time preparing for his lectures, he never read them out from a set of prepared notes or a script, so the only records that we have of what he said are the notes of those who attended. Moore was not the only note-taker at Wittgenstein’s lectures in the early 1930s. Both John King and Desmond Lee took notes at the 1930-32 lectures, and Alice Ambrose took notes at the lectures of 1932 and beyond. Fifty years later, Lee combined his notes with King’s, and published them as one volume (LWL 1980), and Ambrose published her notes in a separate volume (AWL 1979). While both sets of published notes are set out in roughly chronological order, they clearly involve substantial editorial reconstruction, selection, and rearrangement. Where it is possible to compare the record for specific lectures, Moore’s contemporaneous notes are much more detailed, and often significantly different. For instance, the manuscripts of Moore’s lecture notes for the 1932-33 academic year run to about 47,800 words, while the culled and revised version of Ambrose’s notes for those lectures contains about 17,500 words (AWL 1979: 3-40) – i.e. over 30,000 words fewer than Moore’s. It is not merely that Moore’s notes are not simply more detailed than the published student notes from 1930-33; rather, Moore’s notes contain whole discussions that cannot be found in the current editions of Wittgenstein’s lectures.

As well as being significantly redacted, the published student notes of these lectures have sometimes also been heavily edited, rearranged, and tidied up. Lee and Ambrose take a very free approach to their source material, extensively rearranging, modifying and selecting from it in order to provide as readable a version as possible. Cora Diamond’s edition of Wittgenstein’s Lectures on the Foundations of Mathematics, Cambridge 1939 (LFM 1976), which is based on four sets of notes, adopts a similar editorial policy. This is certainly one effective way of collating multiple sets of notes, or of turning a rough set of notes into a readable text (though see Geach 1988 for an alternative method). However, using this editorially heavy-handed method leaves the reader in the dark regarding which words were taken down at the time, and which were reconstructed many years later, with no indication as to where material judged to be repetitive was left out or consolidated, or indeed, when material had actually been added during editing to smooth out the final reading. As Diamond concedes with disarming honesty in her editorial introduction, “choices had to be made with no adequate basis in any version” (LFM 1976: 8). Moore’s original notes allow us to avoid these problems.

Moore’s notes are not only the most detailed; they are probably almost always the most accurate. This is because – for a number of reasons – he was in the position to best understand the lectures. First, unlike any of the other note-takers, Moore had a long-standing personal relationship with Wittgenstein, and they shared a significant philosophical history. They had first become acquainted while Wittgenstein was studying in Cambridge before the First World War; Moore had spent two weeks at Wittgenstein’s cabin in Norway in the spring of 1914 discussing Wittgenstein’s thought. Moore had then been one of the examiners at Wittgenstein’s doctoral defence in the summer of 1929, and had played a leading role in securing fellowship support for Wittgenstein from Trinity College. According to Alice Ambrose, Wittgenstein “respected Moore greatly and had discussions with him ... once a week during term, on a day Moore specially set aside for him” (Flowers 1999: 263.) Second, Moore was a mature and experienced professor of philosophy, while the other note-takers were still students: King and Lee were undergraduates, while Ambrose, who had earned her first Ph.D. at the University of Wisconsin in 1932, was working on a second Ph.D. with Moore and Wittgenstein. Third – and closely related to the previous two points – Wittgenstein seems to have directed the lectures specifically at Moore. According to Karl Britton, “we felt that Wittgenstein addressed himself chiefly to Moore, although Moore seldom intervened and often seemed to be very disapproving ... we had the impression that a kind of dialogue was going on between Moore and Wittgenstein, even when Moore was least obviously being ‘brought in’” (Flowers 1999: 205). Similarly, Desmond Lee recalled that Wittgenstein had a “great personal liking” for Moore, “as well as a great respect [for him] as a philosopher”. Lee further reported that Wittgensein “relied on [Moore] a good deal to help in his discussion classes by making the comment that would set or keep the ball rolling” (Flowers 1999: 195).

Indeed, in April 1932, Wittgenstein wrote to a friend that he was glad Moore was attending his classes, as he doubted that anyone else in the room understood what he was saying: “My audience is rather poor – not in quantity but in quality. I’m sure they don’t get anything from it and this rather worries me. Moore is still coming to my classes which is a comfort”(WC 2008: 203). Furthermore, Moore later recalled that Wittgenstein told him that “he was glad I was taking notes, since, if anything were to happen to him, they would contain some record of the results of his thinking” (MWL 1993: 50).

In his memoir of Wittgenstein, Norman Malcolm reported that Wittgenstein was furious with those who said that he kept his post-Tractatus philosophy secret, for “he had always regarded his lectures as a form of publication”(MAM 1984: 48). It may be thought that in this remark Wittgenstein was thinking primarily of the Blue Book, dictated during the 1933-34 academic year, and the Brown Book, which dates from the following year, both of which circulated privately, in mimeograph or typescript copies, and were widely read by British philosophers. However, it seems clear that Wittgenstein did in fact consider all his lectures to have been a form of publication. He told Casimir Lewy “that ‘to publish’ means ‘to make public’, and that therefore lecturing is a form of publication” (Lewy 1976: xi, fn. 1). Moore’s notes are, therefore, the closest thing that we have to an authorised record of these earliest ‘publications’ of Wittgenstein’s later period – his 1930-33 lectures.

3. Content: Wittgenstein’s Cambridge lectures, 1930-1933, as seen through Moore’s notes

In Moore’s lecture notes we see Wittgenstein presenting his ideas in a setting in which he could take very little for granted. Many of the lectures have a free-flowing, off-the-cuff character; we get to see Wittgenstein working through his thoughts in real time. We see which topics Wittgenstein chose to present to his students, and how he developed them; we see him set out his principal reservations about the Tractatus, and his changing approach to the questions that occupied him at the time. The lectures were an opportunity for Wittgenstein to try out and explore ideas that would go on to make their way into his later writings in a more polished form. There is very little, if any, of the dialectic between different voices that is characteristic of much of Wittgenstein’s post-Tractatus writing. The principal voice in these notes is that of Wittgenstein the teacher, setting out views that he wants to convey to his students or debate with Moore.

However, it would be misleading to suggest that the lectures had a unitary tone or character. Judging by Moore’s notes, Wittgenstein’s approach varied considerably over the course of the nine Cambridge terms attended by Moore. The first two terms’ worth of lectures – which addressed topics in the philosophy of language, mind, and mathematics – were for the most part expository and introductory, and probably covered much of the ground that Wittgenstein would discuss with Russell in May of that year (see WC 2008: 183). The lectures of May Term, 1932 – given under the rubric of “Philosophy for Mathematicians” – were much more formal and technical, and set out ideas that Wittgenstein had probably worked out at some length beforehand. Substantial portions of that term’s notes closely parallel the discussion of inductive proof, periodicity and the infinite in the last two chapters of the Big Typescript. On the other hand, the lectures of the last term of the series, May Term 1933 – which include wide-ranging discussions of topics in the philosophy of religion, ethics, aesthetics, and psychoanalysis – covered topics about which Wittgenstein did not write much elsewhere, and covered them in a way that was often more nuanced, careful, and detailed than what he did write on these topics.

Taken as a whole, Moore’s lecture notes therefore provide a detailed record of Wittgenstein’s treatment of a remarkably wide range of topics: not only logic, language, the philosophy of psychology and mathematics, but also ethics, aesthetics, religion, anthropology, psychoanalysis, and phenomenology. They provide an excellent outline of the development of his thought during the early 1930s, from his criticism of the Tractatus to extensive discussion of Freud’s Jokes and Their Relation to the Unconscious and passages from Frazer’s Golden Bough. The notes not only offer insight into his understanding of the Tractatus, but also introduce many of the issues discussed in the Philosophical Investigations.

4. Text and context: Moore as philosophical note-taker rather than mere amanuensis, and the resultant editorial challenges

Moore was, however, far more than merely an accurate note-taker. He was a colleague of Wittgenstein’s who had his own philosophical reactions to the ideas that Wittgenstein was developing. These reactions are recorded in a number of places. Best known are the series of articles in Mind that Moore published in 1954 and 1955 – a few years after Wittgenstein died – based on the notes he had taken at Wittgenstein’s lectures (MWL 1954a-b, 1955a-b; reprinted in MWL 1993). These articles take the form of an overall summary and analysis of the development of Wittgenstein’s views on a number of topics during the course of the 1930-33 lectures. However, they provide very little direct quotation from Moore’s notes, and are rather selective in the topics that they cover. Furthermore, these discussions of Wittgenstein’s lectures provide rather more coverage of the earlier lectures than they do of the last year that Moore attended, even though over half of his original notes are from that latter period. Not counting the opening pages of Moore’s first piece for Mind, which provide some historical background, the published articles comprise a little over 30,000 words of summary and analysis, while the original lecture notes contain approximately 80,000 words and over 60 diagrams and illustrations.

In the Mind articles, however, Moore does an extraordinary job of organising and systematising Wittgenstein’s sprawling discussions. Moreover, Moore often offers his own views on what Wittgenstein said. Sometimes he points out inconsistencies or peculiarities in Wittgenstein’s claims, or points out where he thinks that Wittgenstein was incorrect. Sometimes he expresses doubt as to whether he understood what Wittgenstein was trying to say, and sometimes he even tries to make seemingly implausible claims of Wittgenstein’s more plausible by offering possible interpretations of what Wittgenstein may have meant. The articles give a palpable sense of Moore puzzling through Wittgenstein’s developing thought. A process which is also manifest in some of the entries in Moore’s Commonplace Book (see Moore 1962, index entry for ‘Wittgenstein, L.’)

An earlier, and less well-known, source embodying Moore’s philosophical engagement with Wittgenstein’s teaching can be seen in a short paper that Moore wrote on Wittgenstein’s use of the phrase ‘rules of grammar’ in February 1932. This paper, which is also part of Cambridge University Library’s Moore collection, was first published as “Wittgenstein’s Expression “Rule of Grammar” or “Grammatical Rule” ” (Moore 2007), and will form an appendix to our edition of Moore’s lecture notes. Moore presented the paper at one of Wittgenstein’s discussion classes to open up the discussion, which was not unusual. Moore later recalled this occasion in the following terms: “I wrote a short paper for him [Wittgenstein] in which I said that I did not understand how he was using the expression ‘rules of grammar’ and gave reasons for thinking he was not using it in its ordinary sense; but he, though he expressed approval of my paper, insisted at that time that he was using the expression in its ordinary sense” (MWL: 69).

Even in the course of transcribing Wittgenstein’s lectures into the six manuscript volumes, Moore was not simply an amanuensis or a recorder of Wittgenstein’s words. In addition to lecture transcriptions, Moore’s notes also sometimes include his own reactions, questions, and clarifications. Comments that are clearly in Moore’s own voice rather than in Wittgenstein’s can be found throughout the lecture notes. For the most part Moore took his notes of Wittgenstein on the right-hand page of his notebooks. The left-hand page was left blank, giving him space for occasional remarks of his own and other notes on the text. Sometimes he speculated about what Wittgenstein meant by a given remark, sometimes he tried to give a concrete example of a more abstract point of Wittgenstein’s, and occasionally he noted where he thought Wittgenstein had made a mistake or gone wrong. Though not extremely common, these comments and markings – when they do exist – provide a record of Moore’s initial response to Wittgenstein’s later thought at its early stages of development.

In these comments and markings, we have a record of two distinct interactions that Moore had with the lecture notes. The first interaction was contemporaneous with the lectures themselves, and can be found in the short comments that Moore made either during the lectures or shortly thereafter. The second interaction occurred twenty years later, when Moore revisited his notes in order to work on his articles for Mind, and in so doing, added further reactions in the form of comments, underlinings, and markings of various kinds. The original comments reveal Moore’s immediate reactions to Wittgenstein’s lectures, while the later additions show him organising and cross-referencing the notes. On occasion, we see the later Moore struggling to recall or work out what Wittgenstein had said twenty years earlier. Thus, the notes include contributions from three authors, as it were: principally Wittgenstein in the early 1930s, but also Moore in the early 1930s, and Moore in the early 1950s.

One challenge in editing Moore’s notes is to distinguish among these three contributions. This is not always a problem. Fortunately, most of Moore’s comments – both early and late – are clearly distinguishable from the content of Wittgenstein’s lectures by their placement in the margins, between the lines, or on the opposite page from the main text. Furthermore, in many cases, Moore’s two sets of interactions with the notes can be distinguished on the basis of physical characteristics of the text, since Moore’s handwriting in the 1950s was less steady than his earlier writing, and because some of Moore’s later additions are in ink while his original notes are all in pencil. Finally, comments written above illegible words are usually Moore’s later clarifications or best guesses of what he originally wrote down. While these patterns are generally reliable, there are a few remarks in the notes that could plausibly be attributed to more than one of the ‘three’ authors.

One of the chief editorial questions about authorship arises in connection with Moore’s use of underlining and other symbols. Moore frequently underlined words or phrases and sometimes put an asterisk next to passages that he did not understand. Underlining sometimes seems to be a means used by Moore during the original note-taking to indicate Wittgenstein’s verbal emphasis on certain words. In other cases, however, underlining probably indicates Moore’s own emphasis, such as when a word is underlined and accompanied by a marginal comment about its meaning. Many question marks at the end of sentences naturally indicate that Wittgenstein has asked a question; others, including most of those in the margins, seem to be expressions of Moore’s later doubts or reservations about what Wittgenstein had said. Similar questions arise with respect to deletions, insertions, corrections, and other changes to the text. Some were clearly written while the lectures were being given – possibly indicating Wittgenstein’s own self-corrections – while others look more like later clarifications added by Moore. So too, arrows connecting two words or phrases might indicate either that Wittgenstein explicitly connected them in the course of his lectures, or that Moore made this connection himself, in the 1950s, when he often cross-referenced passages addressing similar issues, in preparation for writing his Mind articles. Similar uncertainty attaches to the use of diagrams and logico-mathematical notation in the notes. When an apparent syntactical error is found in a logical formula, it is not always easy to determine whether Wittgenstein intended the irregularity, whether Wittgenstein made a mistake which Moore faithfully transcribed from the blackboard, or if Moore introduced the error himself. Finally, when Moore recreates one of Wittgenstein’s diagrams, it is not always simple to determine which marks are essential to the drawing, and which are accidental inkblots or pen strokes.

Fortunately, however, most of these intricate questions of authorship and intention apply only to small details, or to the two layers of Moore’s own comments and markings. For the most part, it is clear what belongs to Wittgenstein and what belong to the note-taker, which is one of the reasons why these notes are so much more valuable than the already published editions of student notes. And the existence of Moore’s remarks and responses have the added value of providing us with a record of the philosophical reactions of one of Wittgenstein’s important contemporaries to the radical newness and unfamiliarity of Wittgenstein’s later thought as it was developing, even if we cannot always know the precise date of every reaction.

While the notes are mostly very well preserved, a few pages have suffered significant wear. The handwriting on these pages is sometimes unclear and occasionally almost illegible. Fortunately, part of Moore’s preparation for his Mind articles included writing an extensive summary of the notebooks on loose pages. In many cases, these verbatim transcriptions provide a detailed reconstruction or transcription of some of the least legible passages in the source text, which can help in deciphering the original notes.

Previous editions of Wittgenstein’s lectures have all been heavily edited, as were almost all of the 20th-century publications from his Nachlass. Unlike those editions, we intend to stay as close as possible to what Moore wrote, while providing the reader with an edition that is easy to follow. Thus our first principle is that the edition should reproduce the manuscript as exactly as possible, only amending it if the benefits yielded by the editorial alteration outweigh the basic value of providing a faithful reproduction. A print edition that included all of the details of a complete ‘diplomatic’ transcription would provide a great deal of information about deletions, insertions, variants and abbreviations that would not only be of no interest to the vast majority of readers, but would also make the text unnecessarily difficult to read. For this reason, we envisage a published text that will be closer to a ‘normalised’ transcription, one that views semantically and philosophically insignificant deletions, insertions, and notes regarding variants as instructions to be used in producing a text that conforms to the author’s intentions, rather than as content to be published. In the few cases in which details – such as deletions – have philosophical significance, we will record them in footnotes. However, because there will be some scholars who would be interested in all the minutiae of Moore’s text, we are planning to publish facsimiles of the manuscript notebooks online, simultaneously with the publication of the normalised print edition.

Producing an accessible text also involves filling out unambiguous abbreviations, and fixing obvious errors in such areas as spelling and punctuation. However, we do not attempt to reorganise the notes or incorporate our own conjectures on how best to fill in the gaps. Doing so would no longer be editing Moore’s text, but producing our own, and would be to negate what is these notes’ chief value: their immediacy and accuracy as a record of Wittgenstein’s teaching.

An edition of Moore’s notes – edited by the authors of this paper – is forthcoming from Cambridge University Press (2015), entitled: Wittgenstein: Lectures, Cambridge 1930-1933, From the Notes of G. E. Moore.

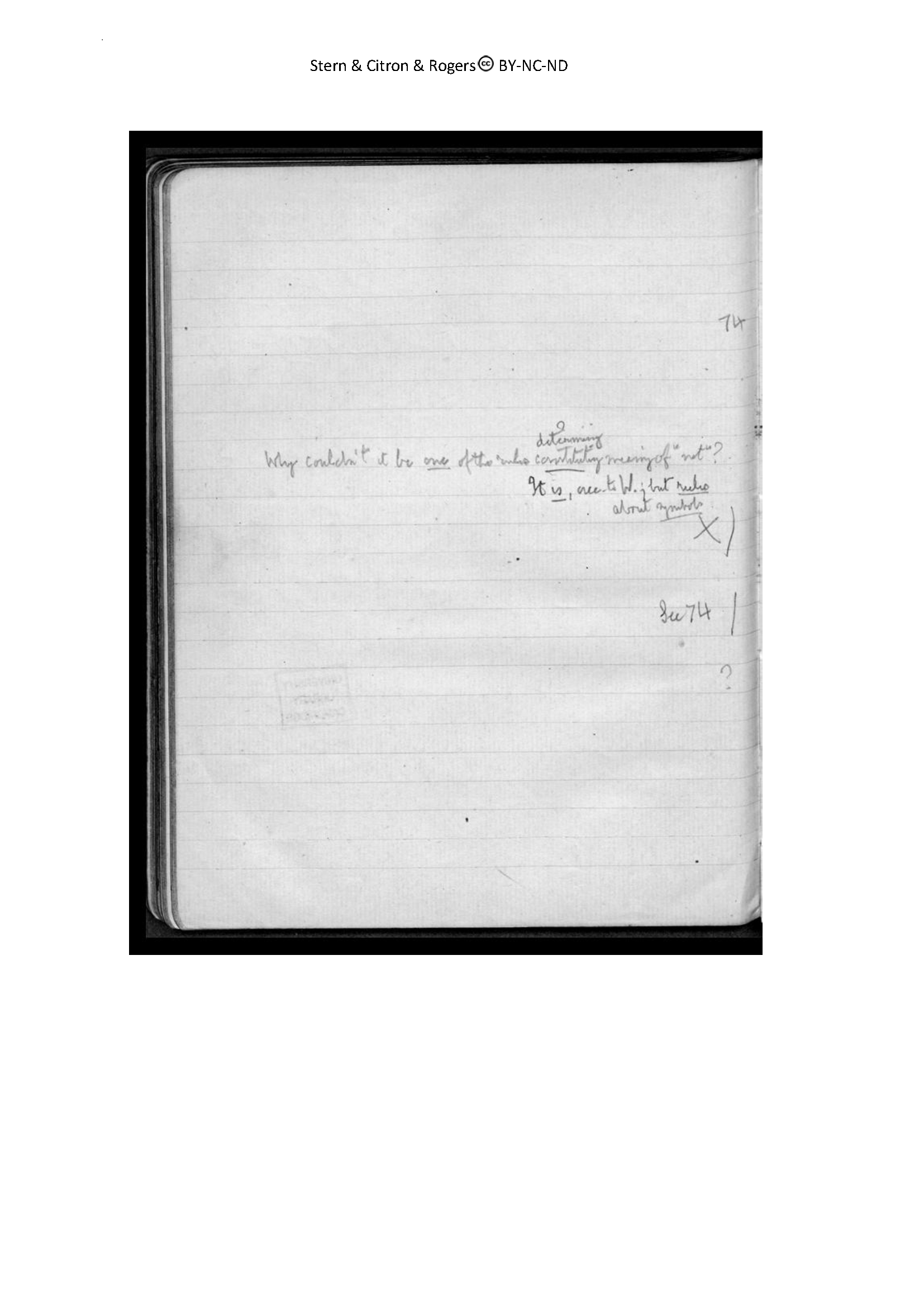

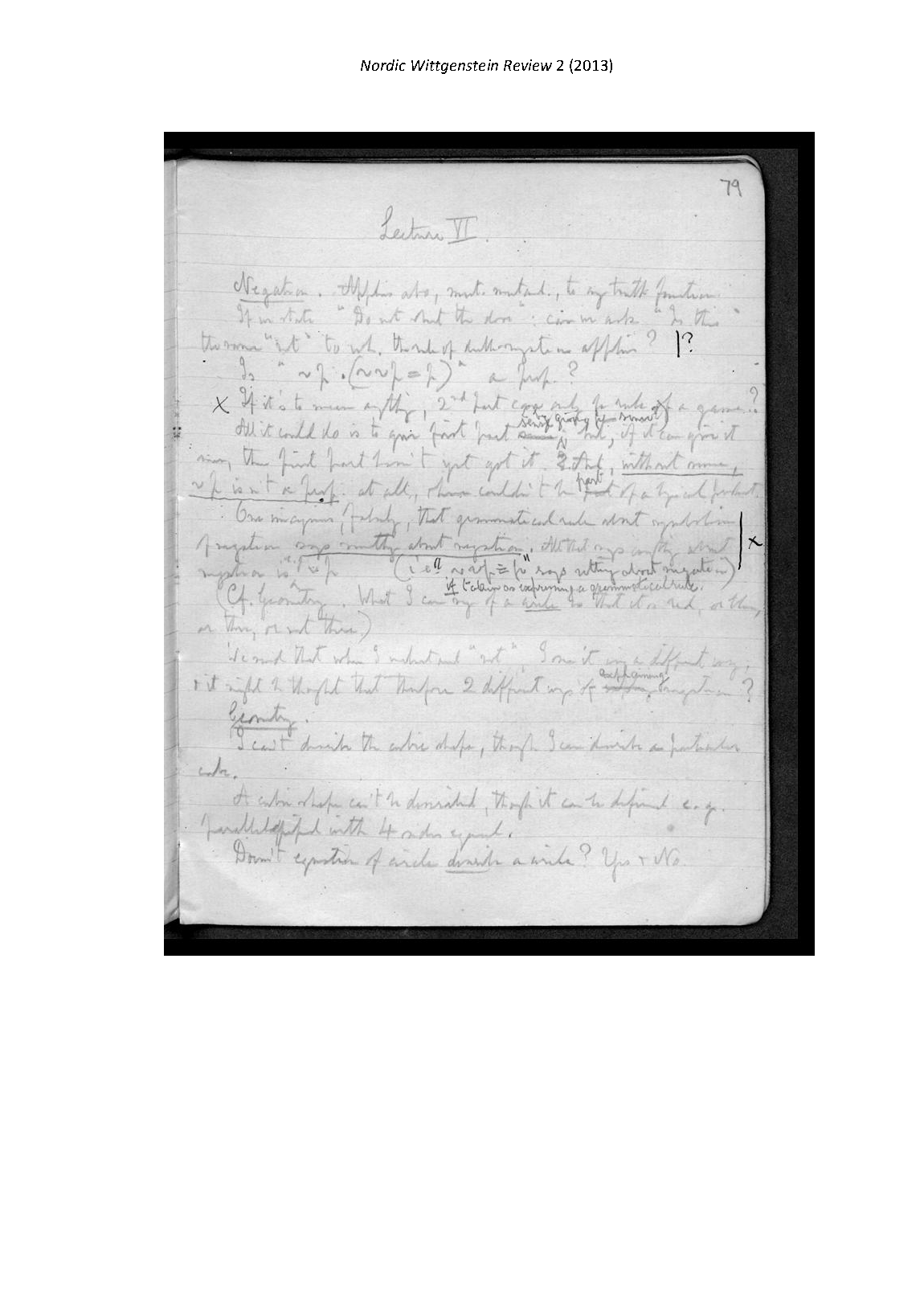

Appendix: Sample Page from Moore’s Notes

The following images of facing pages from a lecture in Lent Term 1931 illustrate some of the features of the notes we have described. The right-hand page includes Moore’s later clarifications of illegible words (on lines 8, 10, and 17), insertions of Moore’s commentary on the lectures (between lines 7 and 8), and crosses and question marks used by Moore to prepare for his summary article. The symbols on lines 10 and 12 are in ink and thus were added later. The parenthetical remark on line 13 appears to have been inserted during the lecture transcription, while the comment inserted between lines 13 and 14 was likely added later, since it is written in handwriting similar to that used in Moore’s notes from the 1950s. The left-hand page includes cross-references to other pages in the notes, editorial symbols, and additional commentary by Moore.

The images are reproduced by kind permission of the Syndics of Cambridge University Library, and of Thomas Baldwin. They are from Moore’s notebook of classmark MS.Add.8875 10/7/5, pp. 78v-79r.

References

Ammereller, E. and E. Fischer, eds. 2004. Wittgenstein at Work: Method in the Philosophical Investigations. London: Routledge.

Baker, G. and P. Hacker, 1980. An Analytical Commentary on Wittgenstein’s Philosophical Investigations. University of Chicago Press, Chicago. Revised second edition, Blackwell, 2005.

Baker, G. and P. Hacker, 1980a. Wittgenstein, Meaning and Understanding: Essays on the Philosophical Investigations. University of Chicago Press, Chicago. Revised second edition, Blackwell, 2005.

Baker, G. and P. Hacker, 1985. Wittgenstein: Rules, Grammar and Necessity. University of Chicago Press, Chicago. Revised second edition, Wiley-Blackwell, 2009.

Citron, G., forthcoming 2013. “Religious Language as Paradigmatic of Language in General: Wittgenstein’s 1933 Lectures”. In: N. Venturinha, ed. 2013, The Textual Genesis of Wittgenstein’s Philosophical Investigations. London: Routledge.

Conant, J., 2007. “Mild Mono-Wittgensteinianism.” In: Crary 2007, pp. 29-142.

Crary, A. (ed.), 2007. Wittgenstein and the Moral Life: Essays in Honor of Cora Diamond. Cambridge, MA: MIT Press.

Crary, A. and R. Read (eds.), 2000. The New Wittgenstein. London: Routledge.

Diamond, C., 1991. The Realistic Spirit: Wittgenstein, Philosophy and the Mind. Cambridge, MA: MIT Press.

Diamond, C., 2004. “Criss-Cross Philosophy.” In: Ammereller and Fischer 2004, pp. 201-220.

Engelmann, M., 2011. “What Wittgenstein’s Grammar is Not (On Garver, Baker and Hacker, and Hacker on Grammar).” Wittgenstein-Studien, volume 2, pp. 71-102.

Engelmann, M., 2013. Wittgenstein’s Philosophical Development: Phenomenology, Grammar, Method and the Anthropological View. Palgrave Macmillan.

Flowers III, F., ed. 1999. Portraits of Wittgenstein, vol. 2. Bristol: Thoemmes Press.

Freud, S., 1960. Jokes and Their Relation to the Unconscious, trans. James Strachey. London: Hogarth Press.

Frazer, J. G., 1922. The Golden Bough: A Study in Magic and Religion (abridged edition). London: Macmillan.

Glock, H., 1996. A Wittgenstein Dictionary. Oxford: Blackwell.

Hacker, P., 1990. Wittgenstein: Meaning and Mind. An Analytical Commentary on the Philosophical Investigations, vol. 3. Oxford: Blackwell.

Hacker, P., 1996. Wittgenstein: Mind and Will. An Analytical Commentary on the Philosophical Investigations, vol. 4. Oxford: Blackwell.

Hacker, P., 2000. “Was he Trying to Whistle it?” In: Crary and Read 2000, pp. 353-88.

Hacker, P., 2012. “Wittgenstein on Grammar, Theses and Dogmatism.” Philosophical Investigations 35, pp. 1-17.

Lewy, C., 1976. Meaning and Modality. Cambridge: Cambridge University Press.

Lütterfelds, W., ed. 2007. Wittgenstein Jahrbuch 2003/2006. Peter Lang.

Malcolm, N., 1984. Ludwig Wittgenstein: A Memoir. With a Biographical Sketch by G.H. von Wright. London: Oxford University Press. [MAM]

Moore, G. E., 1955. “Wittgenstein’s Lectures in 1930-33.” First published in three parts in Mind [MWL 1954a-b, MWL 1955a-b]; reprinted in Wittgenstein 1993, pp. 45-114. [MWL]

Moore, G. E., 1962. Commonplace Book: 1919-1953, ed. Casimir Lewy. London: George Allen & Unwin.

Moore, G. E., 2007. “Wittgenstein’s Expressions ‘Rule of Grammar’ or ‘Grammatical Rule’”, ed. J. Rothhaupt and A. Seery. In: Lütterfelds 2007, pp. 201-207.

Pichler, A., 2004. Wittgensteins Philosophische Untersuchungen: Vom Buch zum Album Studien zur Österreichischen Philosophie 36 (edited by Rudolf Haller). Amsterdam, New York: Rodopi.

Pichler, A., and S. Säätelä (eds.) 2005. Wittgenstein: The Philosopher and his Works. Second edition, 2006. Frankfurt a. M: ontos verlag.

Schulte, J., 2002. “Wittgenstein’s Method.” Wittgenstein and the Future of Philosophy. A Reassessment after 50 Years, eds. Rudolf Haller and Klaus Puhl, pp. 399-410. Hölder-Pichler-Tempsky.

Schulte, J., 2011. “Waismann as Spokesman for Wittgenstein” Vienna Circle Institute Yearbook, Vol. 15 McGuinness, B.F. (Ed.) pp. 225-241.

Stern, D. G., 1991. “The ‘Middle Wittgenstein’: from Logical Atomism to Practical Holism.” Synthese 87, pp. 203-226.

Stern, D. G., 2004. Wittgenstein’s Philosophical Investigations: An Introduction. Cambridge: Cambridge University Press.

Stern, D. G., 2005. “How Many Wittgensteins?” In: Pichler and Säätelä 2005, pp. 164-188; 2006, pp. 205-229.

Stern, D. G., 2013. “Wittgenstein on Ethical Concepts: a Reading of Philosophical Investigations §77 and Moore’s Lecture Notes, May 1933.” Forthcoming in Proceedings of the 35th International Ludwig Wittgenstein-Symposium, edited by Martin G. Weiss & Hajo Greif. Frankfurt: Ontos Verlag.

Stern, D. G., 2013a. “Wittgenstein’s Lectures on Ethics, Cambridge 1933.” Forthcoming in Wittgenstein Studien.

Stern, D. G., forthcoming. “Wittgenstein in the 1930s”. In: H. Sluga and D.G. Stern, eds. The Cambridge Companion to Wittgenstein, revised second edition. Cambridge: Cambridge University Press.

Wittgenstein, L., 1922 Tractatus Logico-Philosophicus, translation on facing pages by C. K. Ogden. Routledge and Kegan Paul, London. 2nd ed., 1933.

Wittgenstein, L., 1953. Philosophical Investigations, ed. G.E.M. Anscombe and R. Rhees, translation on facing pages by G. E. M. Anscombe. Blackwell, Oxford. 2nd ed., 1958. Revised 4th ed., 2009.

Wittgenstein, L., 1958. The Blue and Brown Books. Preliminary studies for the “Philosophical investigations”. References are to the Blue Book or Brown Book. Second edition, 1969. Blackwell, Oxford.

Wittgenstein, L., 1964. Philosophical Remarks, first published as Philosophische Bemerkungen, German text only, ed. R. Rhees, Blackwell, Oxford. 2nd ed., 1975, trans. R. Hargreaves and R. White, Blackwell, Oxford.

Wittgenstein, L., 1969. Philosophical Grammar, first published as Philosophische Grammatik, German text only, ed. R. Rhees, Oxford: Blackwell. English translation by A. Kenny, 1974, Blackwell, Oxford.

Wittgenstein, L., 1976. Wittgenstein’s Lectures on the Foundations of Mathematics, Cambridge 1939, ed. C. Diamond. Ithaca: Cornell University Press. [LFM]

Wittgenstein, L., 1979. Wittgenstein’s Lectures, Cambridge 1932-1935, ed. A. Ambrose. Chicago: University of Chicago Press. [AWL]

Wittgenstein, L., 1980. Wittgenstein’s Lectures, Cambridge 1930-1932, ed. D. Lee. Chicago: University of Chicago Press. [LWL]

Wittgenstein, L., 1988. Wittgenstein’s Lectures on Philosophical Psychology: 1946-47, ed. P. T. Geach. New York: Harvester Wheatsheaf.

Wittgenstein, L., 1993. Philosophical Occasions, ed. J. Klagge and A. Nordmann. Hackett, Indianapolis.

Wittgenstein, L., 2005 The Big Typescript, ed. C.G. Luckhardt, translation on facing pages. Blackwell, Oxford.

Wittgenstein, L., 2008 Wittgenstein in Cambridge: Letters and Documents 1911-1951. Ed. B. McGuinness. Blackwell, Oxford. [WC]

Wittgenstein, L., forthcoming. Wittgenstein: Lectures, Cambridge 1930-1933, From the Notes of G. E Moore. G. Citron, B. Rogers, and D. Stern, eds. Cambridge: Cambridge University Press.

Wittgenstein, L., and F. Waismann 2003. The Voices of Wittgenstein: The Vienna Circle, ed. G. Baker, trans. G. Baker et al. London: Routledge. [VW]

Biographical note

David G. Stern is a Professor of Philosophy and a Collegiate Fellow in the College of Liberal Arts and Sciences at the University of Iowa. His research interests include the history of analytic philosophy, philosophy of language, philosophy of mind, and philosophy of science. He is the author of Wittgenstein’s Philosophical Investigations : An Introduction (Cambridge University Press, 2004) and Wittgenstein on mind and language (Oxford University Press, 1995). He is also a co-editor of Wittgenstein Reads Weininger, with Béla Szabados (Cambridge University Press, 2004) and The Cambridge Companion to Wittgenstein, with Hans Sluga (Cambridge University Press, 1996.) A second, extensively revised, edition of The Cambridge Companion to Wittgenstein is being prepared, for which he is writing a chapter on “Wittgenstein in the 1930s”.

Gabriel Citron is a Junior Research Fellow at Worcester College, Oxford. His research interests include the philosophy of religion, metaphysics, and Wittgenstein. In addition to co-editing Moore’s notes of Wittgenstein’s lectures, he is also engaged in other related editing projects. These include: an edition of Wittgenstein’s marginalia, which is in its early stages; and two sets of student notes of Wittgenstein’s philosophical discussions, forthcoming in Mind: “Wittgenstein’s Philosophical Conversations with Rush Rhees (1939-50): from the notes of Rush Rhees” and “A Discussion Between Wittgenstein and Moore on Certainty (1939): from the notes of Norman Malcolm”.

Brian Rogers received his PhD in philosophy from the Department of Logic & Philosophy of Science at the University of California, Irvine. He has interests in early analytic philosophy, philosophy of logic, and philosophical methodology. In his dissertation, Philosophical Method in Wittgenstein’s On Certainty, he argued that several philosophical methods are found in Wittgenstein’s final writings. His publications include “Tractarian First-Order Logic: Identity and the N-Operator”, The Review of Symbolic Logic, 5(4) (co-authored with Kai Wehmeier). He is currently a J.D. candidate at Stanford University.

Notes

1. Parts of Citron 2013 and Stern 2013 and 2013a draw on this section.

↵