Chomsky and Wittgenstein on Linguistic Competence

Thomas McNally and Sinéad McNally

Abstract

In his Wittgenstein on Rules and Private Language, Saul Kripke presents his influential reading of Wittgenstein’s later writings on language. One of the largely unexplored features of that reading is that Kripke makes a small number of suggestive remarks concerning the possible threat that Wittgenstein’s arguments pose for Chomsky’s linguistic project. In this paper, we attempt to characterise the relevance of Wittgenstein’s later work on meaning and rule-following for transformational linguistics, and in particular to identify and evaluate the potentially negative impact it has on that project. We conclude by arguing that Chomsky’s attempts at defending his individualist or non-communitarian standpoint are undermined by his inability to give a decisive response to Wittgenstein’s attack on logical compulsion.

Table of contents

1. Kripke on Wittgenstein and Chomsky

In Wittgenstein on Rules and Private Language, Kripke presents a reading of the later Wittgenstein that depicts him as a type of sceptic about meaning and rule-following. Aside from the highly controversial exegetical questions that this reading raises, one of its most interesting and largely unexplored features is that Kripke makes a few suggestive remarks concerning the possible threat that Wittgenstein’s arguments pose for Chomsky’s linguistic project.

For example, he writes:

Modern transformational linguistics, inasmuch as it explains all my specific utterances by my “grasp” of syntactic and semantic rules generating infinitely many sentences with their interpretation, seems to give an explanation of the type Wittgenstein would not permit. (1982: 97, fn 77)

In a separate footnote, Kripke singles out the notion of “competence”, which is central to Chomsky’s linguistics and is threatened – if not completely undermined – by the Wittgensteinian considerations:

Nevertheless, given the sceptical nature of Wittgenstein’s solution to his problem … it is clear that if Wittgenstein’s standpoint is accepted, the notion of “competence” will be seen in a light radically different from the way it implicitly is seen in much of the literature on linguistics. For if statements attributing rule-following are neither to be regarded as stating facts, nor to be thought of as explaining our behaviour … it would seem that the use of the ideas of rules and of competence in linguistics needs serious reconsideration, even if these notions are not rendered “meaningless”. (1982: 30-31, fn 22)

His point in this passage seems to be that the notion of linguistic competence is only as legitimate as the notion of rule-following because the former is defined in terms of the latter. The Wittgensteinian challenge to rule-following is thus thereby a challenge to the notion of competence; and this would be the case even if that challenge is not strictly of a sceptical nature.

It is important to note, though, that Kripke also briefly suggests that there may be an important sense in which Chomsky and Wittgenstein are in agreement in their conceptions of language:

On the other hand, some aspects of Chomsky’s views are very congenial to Wittgenstein’s conception. In particular, according to Chomsky, highly species-specific constraints – a “form of life” – lead a child to project, on the basis of exposure to a limited corpus of sentences, a variety of new sentences for new situations. There is no a priori inevitability in the child’s going on in the way he does, other than that this is what the species does. As already said in note 22, the matter deserves a more extended discussion. (1982: 97, fn 77)

There are, then, two main points that Kripke makes in these footnotes regarding the relation between his interpretation of Wittgenstein and Chomsky’s linguistic project. On the one hand, there is the potentially negative impact that Wittgenstein’s discussion has on the core notions in Chomsky’s project, which would at least force a reconsideration of these notions; and on the other hand, there are the features that are common to Chomsky and Wittgenstein concerning linguistic competence, such as broadly speaking that we have certain shared natural inclinations (a shared “form of life”) to extrapolate from a limited learning base in the same ways. The problem is that these two issues are only hinted at in Kripke’s text and have not yet been reconciled.

The importance of addressing these issues is highlighted by Chomsky himself when he writes:

Of the various general critiques that have been presented over the years concerning the program and conceptual framework of generative grammar, this [Kripke’s Wittgenstein’s challenge] seems to me to be the most interesting. (1986: 223)

This leads Chomsky to devote an entire chapter of his Knowledge of Language to responding to the challenge articulated by Kripke. In this paper, we will attempt to clarify exactly what this challenge is supposed to be and why it is relevant to Chomsky’s project; and we will evaluate Chomsky’s response to the challenge. However, as explained in the third section, our approach will be to go back to Wittgenstein’s own writings on meaning and rule-following, and to consider whether there is something there that could be viewed as creating a genuine problem for Chomsky. We will thus use Kripke’s remarks merely to raise some of the relevant questions concerning the relation between Wittgenstein’s and Chomsky’s views on language; but we will return to Wittgenstein himself when assessing this relation. We will argue that Wittgenstein’s arguments do pose a genuine threat to Chomsky’s linguistic project because it presupposes a notion (viz. “logical compulsion”) that Wittgenstein shows to be flawed. In the next two sections, we will give a rather detailed discussion of the way in which Wittgenstein attacks this notion; and in the fourth and fifth sections, we will consider how this poses a problem for Chomsky and evaluate his attempts to respond to it.

2. Wittgenstein’s target: Logical compulsion

In this section we will outline the conception of meaning and rule-following that Wittgenstein attacks in the Philosophical Investigations, before going on in the next section to discuss some of his main arguments against this conception. We will begin by considering Wittgenstein’s approach to the problems relating to meaning and rule-following (particularly in §§138-242).

His central concern in these sections is with the relation between mental states such as understanding, intention, picturing, etc., on the one hand, and the behaviour or states of affairs that “accord” with them, on the other. This preoccupation is apparent from the beginning of this discussion. For example, understanding the meaning of a word seems to be something that happens “in a flash” or at a particular instant. But this is “surely something different from the ‘use’ which is extended in time!” (PI §138). This leads him to enquire into the relation between these two aspects: that which we seem to grasp in an instant when we understand a word; and the use we go on to make of that word over time (see PI §139).

How we go on using a word must “accord” in some sense with what we grasp when we understand the word. For example, applying the word “green” to this apple that I encounter must fit or accord with the meaning of this word that I grasped beforehand, even though my grasp of this meaning did not involve thinking of this or countless other instances of the use of the word. There is an analogous issue regarding other phenomena, such as rule-following and intention. For example, what is the relation between the rule that we grasp and its extended pattern of correct application, or between forming an intention to do something and the behaviour that counts as fulfilling that intention, etc.? Wittgenstein’s main concern throughout these sections is with the confusions that very easily arise when attempting to make sense of these relations.

This confusion is best characterised by considering his distinction between logical and psychological compulsion. Wittgenstein’s first explicit mention of this distinction in the Investigations is in the context of discussing what it means to say that a particular application of a word “forces” itself on us (PI §140). In what sense are we compelled to apply a word in a particular way? Does what we grasp in a flash compel us to apply it in certain ways rather than others? Wittgenstein considers the example of the word “cube” to address these questions. It is possible that when I understand the word, a picture of a cube comes before my mind. But does this compel me to apply it only to objects of a certain shape? It is, Wittgenstein states, “quite easy to imagine a method of projection according to which the picture does fit”, say, a “triangular prism” (PI §139). It would indeed be a non-standard method for applying it, or one that would not normally occur to us, but it is nonetheless conceivable. The point that Wittgenstein makes with this example is that there may be a way of applying a word like “cube” that strikes most of us as natural and hence that we tend to agree on. We apply it to these square-shaped objects and not to these triangular-shaped ones. Call this “psychological compulsion”. We can all be compelled in this sense even though it is in principle possible for there to be a non-standard way of applying it that deviates from it. The confusion arises, according to Wittgenstein, when we attempt to formulate a stronger sense of compulsion – call it “logical compulsion” – that is based on more than merely how we are in fact naturally or psychologically compelled to apply a word.

Is there such a thing as a picture, or something like a picture, that forces a particular application on us; so that my mistake lay in confusing one picture with another?--For we might also be inclined to express ourselves like this: we are at most under a psychological, not a logical, compulsion. And now it looks quite as if we knew of two kinds of case. (PI §140; see also RFM I §118)

At this point, Wittgenstein merely raises the question of whether we can make sense of this stronger sense of compulsion, i.e. whether we are actually acquainted with it.

In the remainder of this part of the Investigations, he proposes arguments that undermine this stronger sense of compulsion. This is a controversial exegetical point; commentators disagree over whether he retains some notion of logical compulsion (one that is stripped of its platonist baggage). A lot of this debate centres on what is at stake in rejecting it, and in particular whether it amounts to holding that there is nothing to distinguish what we agree to be the correct application of a word from what is really the correct application. We shall argue, though, that Wittgenstein does reject the notion of logical compulsion. In sections 4 and 5, we shall focus the discussion on the issue of whether or not Chomsky’s project is reliant upon this targeted notion or conception. The discussion in the next section shall thus allow us to frame the Chomsky-Wittgenstein debate in narrow and manageable terms.

3. Wittgenstein’s arguments against logical compulsion

Although it is quite common to attribute two main lines of argument to Wittgenstein in his discussion of rule-following and meaning, there is no consensus on how to characterise these arguments or their relation to one another (for example, compare Brandom 1994: 20-23 and 26-30, Williams 2007: 62-64, and McDowell 2009: 99-108). The first argument usually attributed to Wittgenstein is a regress argument, designed to show that the assumption that rule-following and meaning require an act of interpretation leads to an infinite regress of interpretations, thus failing to determine the meaning of a term or the requirements of a rule (see PI §§198 and 201). However, our main concern in this paper is not with this regress argument, but with the other Wittgensteinian argument. For convenience, we shall refer to it using Brandom’s label of “the gerrymandering argument” (see Brandom 1994: 26-30), but we do so without sharing his particular characterization of it. This is also the argument that Kripke focuses on in his interpretation of Wittgenstein, and hence the one (or a version of it) that Chomsky attempts to respond to.

Wittgenstein’s gerrymandering argument is also more important in the present discussion because – at least as we shall formulate it – it provides a more plausible argument against the notion of logical compulsion, compared to the regress argument. It is not surprising that there is considerable disagreement concerning the correct formulation of Wittgenstein’s gerrymandering argument because part of the difficulty we face is that it has to be extracted from most of the same set of remarks as the one concerning the regress argument (primarily PI §§185-201). When attempting to formulate it, it is helpful to distinguish two main aspects to the conception of meaning that arise in Wittgenstein’s discussion:

Firstly, that the meaning of a term is an abstract standard for the correct application of the term.

Secondly, that the meaning of a term (as construed in the first aspect) succeeds in sorting the applications of the term into those that accord with this meaning and those that do not.

When taken together, these two aspects amount to what could be called a platonist or realist conception of meaning. Although both aspects are discussed in Wittgenstein’s middle and later period writings, the second aspect is much more prominent. It is the aspect that Wittgenstein addresses in his discussion of the act of meaning as “a queer process”, or an activity that takes place in a “queer kind of medium, the mind” (see PI §196; and BB: 3). One of Wittgenstein’s most well-known characterisations of it is in his discussion of the example of a child being taught how to “Add 2” (see PI §185). The child extends the series as we do up to “1000”, but then diverges from us by writing “1004”, “1008”, etc. Furthermore, the child takes himself to be following the rule he was taught, to be continuing on in the same way. The teacher objects that writing “1004” after “1000” does not accord with the rule of “Add 2” as he meant it to be taken. But now we come up against this mysterious act of meaning because the teacher cannot say that he thought of “1002” as the next step, or thought of “1004” as the step after “1002”, etc. And yet there must be some sense in which writing “1002” rather than “1004” accords with the meaning that the teacher attached to “Add 2”.

The notion of logical compulsion is captured by this distinction between the two aspects of meaning. In particular, it corresponds to the second aspect, or the conception of meaning as determining in advance the pattern of correct application of a term. Furthermore, Wittgenstein’s regress and gerrymandering arguments, and their relation to one another, can now be characterised in relation to this notion. Under one formulation of the regress argument – e.g., that suggested in Brandom (1994: 20-23) and Wright (2007: 491-495) – the regress arises by virtue of the assumption that the interpretation of a sign determines its meaning in the sense of the first aspect above. That is, it is assumed that the act of interpretation fixes a standard for the correct application of the sign. But the regress arises because it is questioned that such meanings or standards themselves can compel (i.e. logically compel) us to apply them in such-and-such a way in particular instances. It is from this questioning of logical compulsion, or the second aspect above, that the need arises for a further meaning or standard for applying it (a standard for applying the original standard of application), but which in turn does not logically compel us and so calls for a further meaning or standard, etc. Hence, this version of the regress argument can only function by directly challenging the notion of logical compulsion.1

Following from this, the gerrymandering argument can also be seen to concern the notion of logical compulsion, but in a more complicated way. Unlike the regress argument, the gerrymandering argument does not directly challenge the notion of logical compulsion. Rather, this argument functions by assuming the legitimacy of this notion, or assuming that meaning something by a word involves “predetermining” or “anticipating” the pattern of correct application of the word (as Wittgenstein’s interlocutor puts it at PI §188). It then proceeds to show that making this assumption leads us into difficulties, and in particular that it leads to the “paradox” stated at §201 that there is “neither accord nor conflict here” because any action can count as according or conflicting. To explain how, we need to reflect for a moment on what would be involved in assuming the legitimacy of the notion of logical compulsion. If this assumption is in place, then – returning to Wittgenstein’s example – we would have to hold that if the child does mean the rule of Add 2 by the expression “Add 2”, then the child should (is logically compelled to) write “1002” after “1000”; and if the child means the deviant rule of Add 2 up to 1000, 4 up to 2000, 6 up to 3000 and so on by “Add 2”, then he should write “1004” after “1000”, etc. But then we can extend this to any person’s use of any term and ask how we can tell that they attach the “standard” meaning to the term rather than some “deviant” meaning that logically compels them to diverge from us in their use of the term. For example, is there some state (e.g., mental state) of the person in virtue of which we can conclude that they have attached the standard meaning rather than the deviant meaning to it? It is difficult to see what such a state would be like and how it could have the relevant meaning-constituting properties.2 It seems, rather, that a person’s having grasped a deviant meaning would only show up when their application of the term starts to deviate from ours and they insist that they are carrying on in the same way. However, now we are facing the paradox that any application of a term that one supposedly understands can be construed as either according or conflicting with how one has always meant that term; i.e. there is always some deviant meaning that we can appeal to as what we meant all along by the term and that logically compels us to apply it in this way that diverges from everyone else. But now the whole notion of according or conflicting with a rule or meaning breaks down because

if everything can be made out to accord with the rule, then it can also be made out to conflict with it. And so there would be neither accord nor conflict here. (PI §201)

The response to this, though, is not to accept this paradoxical conclusion, but (as in the regress argument) to reject the problematic assumption that leads to this conclusion, i.e. to reject the assumption that meaning or rule-following requires the notion of logical compulsion.

To conclude, the relation between Wittgenstein’s gerrymandering argument and the notion of logical compulsion is as follows. The argument assumes that the notion of logical compulsion is legitimate, and thus that understanding a word or following a rule is a matter of being logically compelled to apply the word or rule in particular ways – in accordance with its “predetermined” pattern of correct application. But the only way to maintain this assumption is to avoid the absurd or paradoxical conclusion that anything one does can be construed as applying the word in accordance with its meaning or following a rule; and the most straightforward way of avoiding this conclusion is to identify some distinctive state of the person in which grasping the “standard” meaning rather than the “deviant” meaning consists. In the absence of such a distinctive state constituting the standard meaning, the paradoxical conclusion will be derived and the original assumption concerning logical compulsion will ultimately have to be rejected.

There is, of course, a great deal more that could be said about this central line of argument running through the Investigations, and particularly concerning its relation to the notion of logical compulsion (see McNally (forthcoming) for a more thorough treatment). However, for the purposes of this paper, we will take this interpretive stance on these core features of his work. The challenge to Chomsky will thus be formulated in these very specific terms of identifying such a constitutive state of understanding a word. In the next section, we will consider Chomsky’s linguistic project in relation to this Wittgensteinian challenge.

4. Chomsky, linguistic competence, and Wittgenstein’s gerrymandering argument

Evaluating the potential challenge that Wittgenstein creates for Chomsky is complicated by the fact that there have been numerous manifestations of Chomsky’s project of generative grammar since the late 1950s. In this paper we will narrow our focus to the version often referred to as the “Principles and Parameters” theory (henceforth, “P&P”), first developed in the late 1970s and 1980s and usually considered to be his most significant contribution to linguistics. Many of the core notions associated with his project are present in his earlier work, such as phrase structure rules, the distinction between deep and surface grammar, and universal grammar. But in his P&P theory, these concepts and distinctions are modified and incorporated into a more elegant and powerful linguistic framework. Most notably, universal grammar (henceforth, “UG”) is held to consist of different principles, each of which belongs to a particular “module”, and is applicable to one or more levels of grammatical structure. Some of these universal principles permit of “parametric variation”, which means that they can determine what is grammatical or ungrammatical for particular languages in different ways. For example, the linear order of a phrase head – such as a verb – and its complement is not set by the relevant principle (of X-bar Theory), and is set in one way in English and another in Japanese. The goal of Chomsky’s linguistic project thus becomes that of identifying the universal grammatical principles underlying all languages, as well as the parameters and the kind of parametric variation possible in different languages.

None of this has yet any bearing on the issues raised by Wittgenstein. These rather different perspectives on language become much closer when we consider how Chomsky incorporates this linguistic framework into an account of language acquisition, or of how a person becomes “competent” in understanding and using a particular language. The core notion in this account is that of a “language module” or “faculty of language”. Chomsky’s conception of linguistic competence is in terms of the different possible “states” of the language faculty. There is the state we are born with, or the “initial state”, that contains the principles of UG. The actual learning of a language such as English occurs by being exposed to that language, learning the lexicon and setting the parameters, which are not set in the initial state:

what we “know innately” are the principles of the various subsystems of [the initial state] S0 and the manner of their interaction, and the parameters associated with these principles. What we learn are the values of the parameters and the elements of the periphery (along with the lexicon to which similar considerations apply). (1986: 150)

When we become competent in a particular language, Chomsky holds that our language faculty has arrived at the mature state in which these factors such as the setting of the parameters in particular ways have been realised.3

There are many other aspects to Chomsky’s conception of linguistic competence, such as the kind of knowledge we have of the lexical and phonological properties of the words of a particular language. But in what follows we will focus exclusively on the kind of “syntactical” knowledge that is involved in knowing, e.g., the linear order in which sentences of a particular language must be constructed, in accordance with certain principles and set parameters. For reasons that will become more apparent in the rest of the paper, this central part of his conception of linguistic competence in terms of states of the language faculty is potentially threatened by Wittgenstein’s argument.

To address this, we will first connect it with the discussion of the previous section and consider whether Chomsky’s project presupposes the notion of logical compulsion. Take the example of the “Head-Direction Parameter”. In the Chomskyan P&P account, this parameter is not set by the relevant principle (of X-bar Theory) in the initial state of the language faculty. Depending on the particular language that the child is exposed to, this parameter can be set in one way or another, e.g. in the case of English as “head-initial” rather than “head-final”. Therefore, staying with the case of learning English, it is only in the experiencing of particular examples of English sentences with phrases in which, e.g., the verb-head is prior to its complement that this parameter is set in the child’s language faculty. A significant part of the child becoming linguistically competent thus involves extrapolating from these examples to select the “head-initial” value of this parameter. Becoming competent in this way shapes his comprehension and production of future examples of sentences of various head-complement forms.

This analysis allows us to bring in the distinction between psychological and logical compulsion. If our concern is merely with psychological compulsion, then the only relevant issue is that as a matter of fact most of us tend to extrapolate from a similar learning base in the same way; or in Chomsky’s terminology, that we are all inclined to respond to similar examples of English sentences by selecting the same value for the Head-Direction Parameter, and comprehending and constructing new sentences in accordance with this value. However, with regard to the stronger notion of logical compulsion, there is the further question of the correct and incorrect way to speak and write new examples of English sentences with head-complement form given that the Head-Direction Parameter has been set in a certain way. It seems appropriate to interpret Chomsky’s account as concerned with the notion of logical compulsion, i.e. with the process of setting the parameters for the particular language as determining the correct and incorrect ways of constructing sentences of a certain form in that language. However, we will return to whether this must be the case later in the paper.

As indicated in the discussion in the previous section, there is nothing wrong with presupposing the notion of logical compulsion if Chomsky is able to provide a straight response to Wittgenstein’s gerrymandering argument. This is because Wittgenstein takes this notion to be problematic on the grounds that no state of the person (e.g. a distinctive kind of mental state) can be found that satisfies the criteria of logical compulsion. But if Chomsky can give an account of such a state, in virtue of which we are logically compelled to apply a word or construct a sentence in such-and-such a way, then he will have a straight response to Wittgenstein’s argument. Can Chomsky, then, use his account of linguistic competence to provide such a response to Wittgenstein’s gerrymandering argument? To answer this, we should consider how a response provided in the Chomskyan framework would look.

It is quite easy to formulate the challenge posed by the gerrymandering argument within the Chomskyan framework. Imagine that a person – whose production of English sentences with verb-phrases and their complements has until now conformed to ours – suddenly says:

Other people may correct him by saying that “gave” (the verb-head) should occur at the beginning of the sentence. But if the person cannot see how this differs from how he used it in other instances and insists that he is just continuing to construct sentences in the way he was taught, what are the others to say? The situation is analogous to the child who, after been given the instruction to “Add 2”, deviates from us after “1000” by writing “1004”. In the Chomskyan case, we could say that the person has understood the head-complement word-order to be “head-initial” prior to a certain time, and “head-final” after that time (or perhaps to be head-initial except in cases where a book is being talked about, etc.). Similarly to the Wittgenstein example, there is what we could call a standard way of understanding the order and a non-standard or deviant way. And the fact that the person has understood it in a deviant way only shows up in certain circumstances or after a certain time. The challenge that Wittgenstein’s gerrymandering argument poses is to identify a state of the person, i.e. a state of his language faculty, that shows that his linguistic competence is such that he has set the Head-Direction Parameter in a standard way rather than a deviant way.

The problem for Chomsky is that there is nothing further that he can appeal to in responding to this challenge. He can hold that there is a certain mature (I-language) state of child’s language faculty in virtue of which saying “I the book to John gave” is incorrect or ungrammatical. But the only evidence that Chomsky can appeal to in support of this view is indistinguishable from the evidence that could be appealed to in support of the alternative view that the child has set the parameter in the deviant way. Therefore, Chomsky’s elaborate account of linguistic competence does not have the resources to give a straight response to Wittgenstein’s gerrymandering argument. The conclusion that anything that anybody says or writes can be justified according to some (admittedly deviant) conception of the setting of the parameters cannot be avoided; and so it turns out that Chomsky’s commitment to the notion of logical compulsion is indeed problematic.

The discussion in this section has been at a quite general level. In the next section, we will consider Chomsky’s main attempts at responding to the Wittgensteinian challenge (as he understands it) to his linguistic programme.

5. Chomsky’s individualism and logical compulsion

To delve deeper into the issues raised in the previous section, it will be instructive to consider them from the perspective of how Chomsky himself views the threat posed by Wittgenstein’s arguments. According to Chomsky, the feature of his linguistic account that is potentially most vulnerable is its individualist standpoint, or “the ‘individual psychology’ framework of generative grammar” (1986: 226). More specifically, this feature is threatened by the argument against “private language” that Kripke maintains is a consequence of Wittgenstein’s reflections on rule-following and meaning. Chomsky thus devotes a considerable part of his chapter on Wittgenstein to defending his individualist conception against this threat.

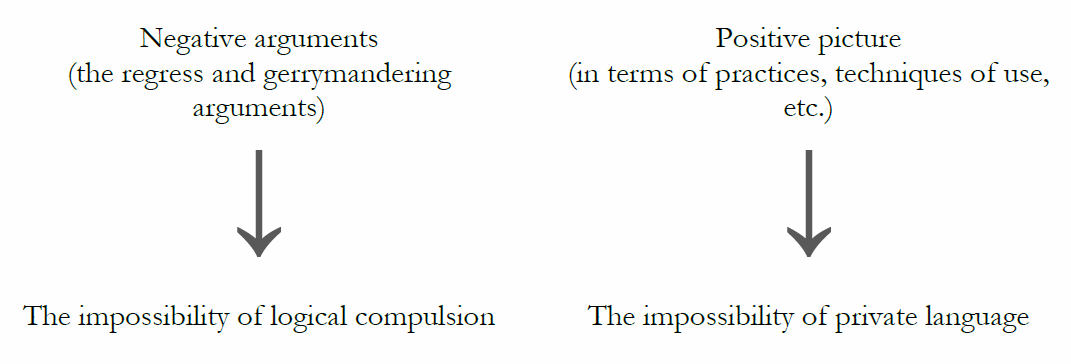

However, this diagnosis of the Wittgensteinian challenge conceals a number of separate issues that must be distinguished before we proceed. First and foremost, we should make a distinction between Wittgenstein’s negative arguments concerning meaning and rule-following (primarily the regress and gerrymandering arguments discussed in section 3), on the one hand, and Wittgenstein’s positive view of our everyday practices of using words and following rules, on the other. Thus far, we have not discussed Wittgenstein’s positive-sounding remarks that invoke, e.g., the notions of practices, customs, and techniques of use. Kripke interprets Wittgenstein’s emphasis on practices and customs of use in terms of adopting a different perspective on language, viz. a move away from the concern with identifying states of the person that are constitutive of rule-following and meaning, and instead focussing on the conditions under which we take someone to be justified in asserting that he or someone else follows a rule or means something by a term (see 1982: 72-78). The only feature of this aspect of Kripke’s interpretation that we want to highlight is that he takes Wittgenstein to be adopting a communitarian conception of language because the “assertability conditions” for statements concerning rule-following and meaning make “reference to a community” (1982: 79). According to Kripke, then, Wittgenstein responds to the negative conclusions of his arguments by proposing a rough communitarian conception of meaning and rule-following. Furthermore, one of Kripke’s main interpretive claims is that the impossibility of private language follows as a “corollary” from this communitarian conception because the reference to the community in the assertability conditions make ascriptions of meaning and rule-following “inapplicable to a single person considered in isolation” (Ibid.).

Assuming for the moment that this is correct, the following figure would represent the relation between these central features of the Wittgensteinian discussion:

As discussed in the third section, Wittgenstein’s negative arguments target the notion of logical compulsion. But one of the crucial features of this picture of Wittgenstein’s philosophy is that the impossibility of private language follows from the positive communitarian conception of language, not from the negative arguments or the conclusion that rejects logical compulsion.

This analysis of how the different parts of Wittgenstein’s discussion relate to one another complicates matters because, as noted a moment ago, Chomsky seems to view his main task as that of responding to the private language argument. Hence, Chomsky’s emphasis on the private language issue potentially misses the main point, or misidentifies the main threat to his project. We will attempt to clear this issue up in this section. We will focus most of the discussion on Chomsky’s response to the Wittgensteinian private language argument. It will turn out, though, that both the issue of logical compulsion and that of private language will be relevant when ultimately deciding the debate between Chomsky and Wittgenstein. Our approach in this section will be to initially take it for granted that Kripke is right about Wittgenstein’s positive conception, i.e. that he has such a conception and that it is communitarian. This, in any case, is how Chomsky views it and he responds to it as such. In the course of our discussion and the evaluation of Chomsky’s response, we will provide support for this communitarian reading.

Chomsky begins his counter-argument to the Wittgensteinian communitarian conception by outlining a number of different cases in which there are genuine instances of rule-following, but there is no communal agreement in how the rule should be applied. For example, Chomsky argues that a Robinson Crusoe from birth or a radically socially isolated individual can be viewed as following rules. He interprets Kripke’s claim that “Our community can assert of any individual that he follows a rule if he passes the tests for rule following applied to any member of the community” (1982: 110) as meaning that if we consider Crusoe as a “person” and “take him into the broader community of persons”, then we can attribute rule-following to him even though his responses are different to ours (Chomsky 1986: 230-231). In such a case, we can call Crusoe a rule-follower, although it may not be clear exactly what rule he is following. Chomsky, though, holds that this is merely an “exotic” example of private rule-following, and that there are numerous “standard” or “normal” cases. These more mundane cases include cases such as the following:

Suppose that we have visitors from a dialect area different from ours… where people say “I want for to do it myself” or “he went to symphony” instead of “I want to do it myself” and “he went to the symphony”. Again, we would say that they are following rules, even though their responses are not those we are inclined to give, and we do not take them into our linguistic community in these respects. (1986: 228)

The common feature of these examples is that they are, for Chomsky, genuine instances of rule-following even though the individual or group does not agree with us in their responses or in how they follow the rules.

The inapplicability of the Wittgensteinian communitarian conception to these cases of rule-following is, according to Chomsky, a major shortcoming of that conception. However, Chomsky does not leave the issue there. He suggests a way in which the Wittgensteinian argument could be extended to incorporate these cases. Chomsky states that there is an ambiguity in Wittgenstein’s notion of “form of life” that may be exploited to save him from this objection. Wittgenstein never gives a rigorous characterisation of this notion, but in such distinctions as that between “agreement in opinions” and agreement in “form of life” (PI §241), and its association with the fundamental notion of “language game”, it is evidently supposed to convey the practical dimension of language and our pre-reflective tendencies or inclinations, or perhaps what comes natural to us when using language. Drawing on Kripke’s discussion, Chomsky makes a distinction between two senses of form of life (see 1986: 232-234). The first sense is narrower and pertains to “the set of responses in which we agree”. This forms the basis of the communitarian conception because somebody will be said to share our form of life in this sense only if they tend to agree in how we follow rules. When this narrow sense is presupposed, the Crusoe and other cases cannot be accommodated because they do not share our responses. But, Chomsky maintains, there is a broader notion of form of life that is based on “the highly species-specific constraints that lead a child to project, on the basis of exposure to a limited corpus of sentences, a variety of new situations” (1986: 232; quoted from Kripke 1982: 97, fn 77). And when the notion is understood in this broader sense, Crusoe and the other cases can be accommodated because the individuals can be held to share in our form of life as members of the same species.

But, Chomsky continues, a major consequence of this modification of the Wittgensteinian framework to accommodate these cases is that the private language argument is “defanged” because numerous cases of private rule-following will have been allowed (see 1986: 233). Therefore, the objection to Wittgenstein can be summarised in terms of a dilemma: either Wittgenstein’s framework is implausible because it excludes numerous legitimate cases of rule-following (including the Crusoe case); or it can be rendered plausible by expanding the framework to include these cases, but then the impossibility of private language cannot be held to follow from it.

One obvious response to Chomsky is to look closer at the apparent counterexamples to the communitarian conception and consider whether they are genuine instances of rule-following. As we saw, Chomsky’s discussion of the Crusoe case is based on placing it in the same category as what he calls certain standard cases. However, there is a clear difference between them. Whereas all of his examples of the more mundane or “normal” cases involve groups of individuals or communities that are rule-followers despite having responses different to ours, Crusoe differs from us in the more radical sense of not sharing our responses but also not belonging to any community. Given his individualist standpoint, it is not surprising that Chomsky considers this difference to be of no importance. But we shall argue that when we look closer at the Crusoe case, the individualist framework in which it is placed becomes problematic in light of the issue concerning logical compulsion that we considered in the previous sections.

When discussing the Crusoe case, Chomsky explains his status as a rule-follower in terms of the different states of his language faculty:

In our terms, we assume that [Crusoe] has a language faculty that shares with ours the state S0 and attains a state SL different from ours, on the basis of which we can develop an account for his current perceptions and actions. (1986: 240-241)

In this Chomskyan framework, Crusoe’s linguistic competence or status as a rule-follower is explained by the transition from the natural initial state of the language faculty to the mature state in which he follows rules, which is mediated by the experience he happens to have. But now the familiar questions can be asked concerning the legitimacy of ascribing rule-following to him. That is, we can ask the same questions about the rules Crusoe follows as we can ask about any individual. And the appeal to states of the language faculty is not sufficient in this response, any more than they are in relation to an individual who is a full-fledged member of a community.

Another way of characterising the shortcoming in this appeal to states of the language faculty is to say that it does not enable Chomsky to distinguish the grasp of deviant rules from the grasp of a standard rule. There are, though, passages in Chomsky’s chapter on Wittgenstein in which he suggests that this does not create a problem for him. For example, when discussing the cases of communities that differ from us in how they follow rules, he states that “there is no question of ‘correctness’ any more than in the choice between English or French” (1986: 228-229). Similarly, he also states that the rules of a person’s language

entail nothing about what Jones [the user of the language] ought to do (perhaps he should not observe the rules for one reason or another; they would still be his rules). And the question of the norm in some community is irrelevant for reasons already discussed. (1986: 241)

This suggests the rather strange position that the notions of correctness or incorrectness are not relevant to how a person applies a word or rule. It would follow from this that even if someone has grasped a deviant rule (or parameterised the universal grammatical principles in a deviant way) that leads him to diverge from us in his use of words and construction of sentences, we should not say that he has done something incorrect; and the fact that the community disapproves of his divergent behaviour is irrelevant. However, these passages could also be interpreted as expressing Chomsky’s radical individualism, i.e. that there are correct and incorrect ways of using words, but they derive solely from the individual’s language faculty and the rules he employs. They do not derive from the community. In other words, we do not have to call the individual who diverges from us in his use of language incorrect as long as what they are doing accords with the rule that the individual has grasped, or with the way in which they happen to have parameterised the grammatical principles.

This view, though, is reduced to absurdity by Wittgenstein’s gerrymandering argument. If anything anybody does in using a word, constructing a sentence, etc., can be justified by appealing to some privately grasped rule or deviant way of setting the parameters, then the whole notion of correctness and incorrectness dissolves. Furthermore, this negative argument can be appealed to in response to any of the counterexamples to the communitarian conception. Any such counterexample would, it seems, have to presuppose the notion of logical compulsion, thus leaving it vulnerable. Ultimately, then, it is Chomsky’s reliance upon this notion that weakens his attempted defence of the “individual psychology” standpoint of his linguistics.

6. Conclusion

Despite what we have argued in this paper, it would be too hasty to conclude that Chomsky’s project is undermined by Wittgenstein’s arguments because there is more that needs to be explored both in relation to the interpretation of these arguments and the details of Chomsky’s linguistics. This paper has consisted in articulating what the Wittgensteinian challenge would amount to when certain of his arguments are interpreted in a particular way (i.e. as targeting the notion of logical compulsion). However, a full defence of this interpretation requires more discussion than can be provided here. The interesting thing about Chomsky’s exchange with Wittgenstein and Kripke is that it allows us to engage concretely with the question of whether a research project such as his could be undermined on philosophical grounds, i.e. whether it must consider and respond to objections very different to those generated from empirical research into language use and language acquisition. This paper has provided a sort of blueprint for dealing with this question by attempting to pinpoint the exact issue on which their disagreement rests, as well as making a start on addressing it.

By way of pointing towards further research on this topic, it will be useful to note that there are certain issues that seem to be pertinent in this context but that have not been directly explored here (although what we have discussed has significant bearing on them). For example, since the publication of Kripke’s reading of Wittgenstein, there has been considerable debate concerning the issue of “semantic normativity” (see, e.g., Wikforss 2001 and Boghossian 2005). Simply put, the issue has to do with whether the meaning of a word – that which we grasp when we understand it – entails obligations for how that word ought to be applied in particular instances, obligations moreover that are intrinsically semantic and not reducible to other kinds of norms. This issue could potentially illuminate the Chomsky-Wittgenstein debate because Wittgenstein’s discussion of meaning and Chomsky’s response both appear to implicitly engage with it. On the one hand, the notion of semantic normativity seems to be closely connected with that of logical compulsion because the latter involves the pattern of correct application of a word being determined in accordance with its meaning (that which we grasp “in a flash”) and being compelled to apply it in accordance with how it is so determined. On the other hand, as discussed in the previous section, part of Chomsky’s response to Wittgenstein is to argue that the rules of a person’s language “entail nothing about what [the person] ought to do” (1986: 241). Therefore, if there is this close connection – or perhaps even equivalence – between the notions of semantic normativity and logical compulsion, it may turn out that Wittgenstein and Chomsky are actually in agreement in their opposition to these notions.

This is merely a suggestion and requires a separate discussion. Even if it turned out to be correct, though, Chomsky would face the challenge of characterising his conception of linguistic competence without relying on a notion such as logical compulsion. This is not a problem that Wittgenstein would face because he is not engaged in anything like the explanatory project of Chomskyan linguistics. Therefore, if we were to pursue the possibility that they are both opposed to the notion of logical compulsion, there would nevertheless be significant disagreement between them on other central points. Addressing this further would help us to elaborate on Kripke’s suggestion (1982: 97, fn 77) that there may in fact be common ground between the standpoints of Chomsky and Wittgenstein on language, as well as to appreciate the significance that these seemingly very different standpoints have for one another.

References

Boghossian, P., 2005. “Is Meaning Normative?” In: A. Beckermann and C. Nimtz, eds. 2005. Philosophy – Science – Scientific Philosophy. Paderborn: Mentis, pp. 220-240.

Brandom, R., 1994. Making It Explicit. Cambridge, MA: Harvard University Press.

Chomsky, N., 1986. Knowledge of Language. New York, Westport, CT, London: Praeger.

Chomsky, N., 2005. “Language and the Brain”. In: A. J. Saleemi, O-S. Bohn, and A. Gjedde, eds. 2005 In Search of a Language for the Mind-Brain: Can the Multiple Perspectives be Unified? Aarhus: Aarhus University Press.

Kripke, S., 1982. Wittgenstein on Rules and Private Language. Cambridge, MA: Harvard University Press.

McDowell, J., 2009. The Engaged Intellect: Philosophical Essays. Cambridge, MA & London: Harvard University Press.

McNally, T., forthcoming. Wittgenstein’s Master Arguments.

Wikforss, Å., 2001. “Semantic Normativity”. Philosophical Studies, Vol. 102, pp. 203-226.

Williams, M., 2007. “Blind Obedience: Rules, Community, and the Individual”. In: M. Williams, ed. 2007. Wittgenstein’s Philosophical Investigations: Critical Essays. Plymouth: Rowman and Littlefield. Ch. 3.

Wittgenstein, L., 1956. Remarks on the Foundations of Mathematics. G. H. von Wright, R. Rhees, and G. E. M. Anscombe, eds., trans. G. E. M. Anscombe. Oxford: Blackwell.

Wittgenstein, L., 1958. The Blue and Brown Books. Oxford: Blackwell.

Wittgenstein, L., 2001. Philosophical Investigations. 3rd ed. Trans. G. E. M. Anscombe. Oxford: Blackwell.

Wright, C., 2007. “Rule-following without Reasons: Wittgenstein’s Quietism and the Constitutive Question”. Ratio, Vol. 20, pp. 481-502.

Biographical note

Thomas McNally’s research is focussed primarily on Wittgenstein’s later philosophy and its connection with contemporary debates in the philosophy of language. He completed his PhD at Trinity College Dublin on the topic of Wittgenstein, Kripke, and scepticism about meaning.

Sinéad McNally is a research psychologist specialising in psycho-linguistics and child psychology. Her doctoral research investigated behavioural and developmental theories of language development. She is currently a Research Associate at the School of Psychology, Trinity College Dublin.

Notes

1. Note that this formulation of the regress argument is different from the one characterised, e.g., by McDowell (2009: 81-86) as involving a regress of signs or meaningless expressions, rather than a regress of semantic entities. Both of these formulations are supported by different passages in Wittgenstein, but we focus on the case of a regress of semantic entities because it engages more explicitly with the notion of logical compulsion. For a more detailed treatment of Wittgenstein’s regress argument, see McNally (forthcoming).

↵ 2. Most of Chapter 2 of Kripke’s (1982) is devoted to considering different candidates of such states and showing that they cannot be constitutive of meaning in the relevant sense.

↵ 3. See Chomsky (2005: 145) for a more recent statement of this conception of linguistic competence in terms of states of the language faculty.

↵